GIL (Global Interpreter Lock) is a mechanism in CPython to synchronise the Python bytecode execution to run only in a single thread at a time. It constitutes a straightforward CPython implementation but becomes obstacles of parallelism in Python. Retrospective endeavour in removing GIL did not reward well. Most of the time the workaround options are multiprocessing, an expensive fork with an opaque copy-to-write mechanism, and C / C++ extension, e.g. Cython.

Sam Gross’s nogil proposal

In 2021, Sam Gross submitted a proposal in Python core maillist to remove GIL in a PoC implementation in Python 3.9. At first, it did not seem to receive welcoming responses from the core developer team. After a few days, Sam explained his design and PoC implementation (in the thread and private) and the appetite in the thread changed. Now it has received spotlight attention whether the PoC change will bring an end to Python infamous limitation in multithreading.

Basically there are two main parts of his changes

- Freeing GIL

- Accompanied with unrelated changes to speed up the main branch CPython

The latter part has been upstreamed to Python 3.10 and 3.11, and it gives a great improvement in Python runtime. So the question is whether the core development team will apply his former nogil change into the future CPython main branch.

Quick glance on nogil design

The design is mainly around maintaining a thread-safe object state and accessing objects without sacrificing much performance.

Memory allocation

The PoC project replaces the thread-unsafe pymalloc by the thread-safe lightweight allocator mimalloc.

Reference count

In current CPython, if an object’s reference count becomes zero, the object is deallocated. The nogil design covers the “biased reference counting” (Choi, 2018) to

- avoid expensive atomic operations always

- modify a “local” reference count with non-atomic instruments in owning thread

- modify a “shared” reference count with atomic instruments in other threads

Immortalization and deferred reference counting are employed to expedite accessing the objects, to compensate for the overhead introduced in reading frequently accessed objects in multithreading.

Immortalization is used in lightweight singleton objects (like small integers and internal strings), the objects like top-level functions, code objects, and modules are deallocated only during garbage collection.

Garbage collection

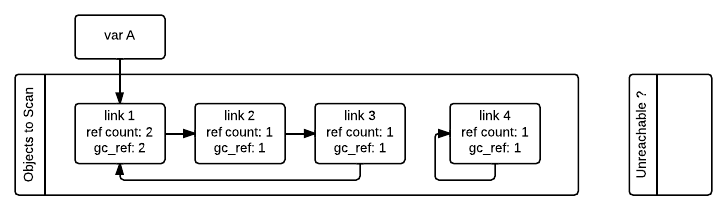

Currently, the garbage collector (GC) handles the cyclic references with which reference counting is unable to track.

The nogil change moves away from the original global linked-list of objects tracked by GC

- GC stops the world at a safe point to scan each each block in heap (allocated by the newly introduced mimalloc) to find GC-tracked objects

- the linked-list of objects are constructed during the scan of leap, rather than maintaining a shared linked list in a thread-safe manner

Collection thread-safety

The PoC implements thread-safe collections on the list and dict classes with a special algorithm to allow fast read / access to their items. Queue collection is modified with fine-grained locking while the other collections are not yet covered.

My experiment

The experiment is to address the following questions

- Does Sam’s nogil version perform as good as it describes?

- Does it support most Python packages?

- Can it be deployed to run production applications now?

1. Does Sam’s nogil version perform as good as it describes?

Answer: Yes or no.

I used the same performance test from Sam Gross’s design documentation to run both Python 3.9 and nogil’s version in pyperformance. Since I had a hard time building the nogil version from the source in my MacBook, I used GitHub’s Action with Docker image to produce the result.

The package pyperformance is originally used for the Python development community to benchmark on read-world examples for all Python implementations. The benchmark includes a few groups. For example, the group app tests on high-level applicative components, e.g. Tornado HTTP.

Regarding the benchmark result in the document,

The new interpreter (together with the GIL changes) is about 10% faster than CPython 3.9 on the single-threaded pyperformance benchmarks.

And when I look back the total elapsed time of my result, the total elapsed time between them are only in modest difference (24 mins with GIL v.s. 25 mins without GIL)

python-gil.json

===============

Performance version: 1.0.5

Report on Linux-5.15.0-1019-azure-x86_64-with-glibc2.31

Number of logical CPUs: 2

Start date: 2022-09-23 19:58:04.774574

End date: 2022-09-23 20:21:51.237614

python-nogil.json

=================

Performance version: 1.0.5

Report on Linux-5.15.0-1019-azure-x86_64-with-glibc2.31

Number of logical CPUs: 2

Start date: 2022-09-23 20:24:36.297722

End date: 2022-09-23 20:49:46.225375

I am scratching my head.

In Sam Gross’s design documentation,

A few caveats: First, the performance improvement is an average (geometric mean across ~60 benchmarks). Some benchmarks run much faster, and a few runs slower than upstream.

Okay, that’s the trick of benchmarking - geometric mean on the performance improvement

Second, the new interpreter stripped of the GIL changes would be even faster on single-threaded workloads

My understanding is those changes are already merged into Python 3.10 and 3.11.

Finally, there are still some use cases that don’t scale well, but I think these cases are easier to address with the new design.

Fair enough. We can’t expect too much from a preliminary change.

In general, from the result breakdown,

- nogil version performs better in I/O related benchmark, e.g.

tornado_http,logging_* - nogil performs worse in mathematical computation, e.g.

scimark_sparse_mat_mult,telco

The results address getting rid of GIL indeed improves I/O performance, but on the mathematical computation, I doubt biased reference counting overrides the benefit of running without GIL. The full result can be found in the task Compare result in the docker run.

In summary, from the benchmark of the proof-of-concept implementation, it opens up both the potential and questions to the project. Will running production applications, like web server / client, give an excellent result without gil?

2. Does it support most Python packages?

Answer: Yes, but not entirely.

TL;DR Most libraries are installable in nogil Python, but not for those requiring extension compilation, especially those written with C / C++ extension.

I experienced the following cases when installing packages for benchmark

-

When the nogil build wheel can’t be found, it needs to download the universe wheel (py2.py3-none-any) and build / compile from scratch. In general, it takes much longer time to install the packages and their dependence.

-

Sometimes the compilation involves other compilers, for instance, Rust compilers, in universal wheel. Without installing the necessary dev libraries in your machine / container, installing those packages will hit the wall.

-

Likely to fail in installing the latest packages of which the installation requires Cython > 3, as currently Cython community has only published nogil wheel in 0.29.x

-

Only limited versions are available in the C / C++ extension built library. For example, Numpy community has built a few versions of nogil packages (1.18.5, 1.19.3, 1.19.4, 1.22.3)

3. Can it be deployed to run production applications now?

Answer: Yes, but I don’t see much benefit in performance.

Now his work can definitely be built from source. You can also get its Python 3.9.10 diverged version from pyenv or docker. I use the docker image to run the benchmark test cases.

Regarding the pyperformance benchmark result, I am driven to test on the real world applications, especially the I/O intensive or web service applications, to examine how well the preliminary nogil Python performs.

Cryptofeed

The first target is on a websocket client. I tested running cryptofeed, a crypto exchange data feed handler. one of my favourite crypto projects in Github. It is an amazing project to illustrate how an enterprise level of feed handler should be developed. Though the project is written in Python, rather than conventional languages like C / C++ for a performance sensitive application, it leverages on uvloop for asynio event loop.

Since no nogil wheel is built on Cython > 3, I had no luck to install the uvloop required in the recent versions of cryptofeed, so I downgraded to install an early version of cryptofeed, using standard library asyncio, to kick start my work.

The following benchmark measures the processing time in cryptofeed (from receipt timestamp to callback time) in microseconds. They are run in docker containers installed with Python 3.9.10 and Python 3.9-nogil. The test simply connects to a single exchange and listens to the trades of a few instruments.

GIL Python 3.9.10 runtime

Runtime summary

=======================

Number: 200

Median: 119

90-pct: 184

95-pct: 226

99-pct: 246

no-GIL Python 3.9.10 runtime

Runtime summary

=======================

Number: 212

Median: 891

90-pct: 1340

95-pct: 1385

99-pct: 1567

I am staggered that the GIL version (around 120 us in median) runs 4x faster than the no-GIL version (around 890 us in median).

Flask

Then I moved on to a standard web client Flask. The main reason I test on Flask is its plain implementation and thin layer of asyncio components. I understand that its performance is far beyond the current market standard and most Python web service applications have migrated to modern frameworks, for example, fastapi. However, if the development team still sticks on Flask framework, it likely means the team has no resources to move forward, and pray a trivial infrastructure upgrade can still keep the legacy applications in the game.

Again the benchmark was run in docker images. The testing application only contains one endpoint /ping and wrk measures the response time of a pool of requests to the server.

GIL Python 3.9.10 runtime

wrk --duration 30s --threads 10 --connections 300 http://127.0.0.1:8000/ping

Running 30s test @ http://127.0.0.1:8000/ping

10 threads and 300 connections

Thread Stats Avg Stdev Max +/- Stdev

Latency 141.28ms 136.63ms 1.62s 97.06%

Req/Sec 105.49 42.11 212.00 61.46%

16469 requests in 30.10s, 2.76MB read

Socket errors: connect 57, read 179, write 0, timeout 141

Requests/sec: 547.06

Transfer/sec: 94.03KB

no-GIL Python 3.9.10 runtime

wrk --duration 30s --threads 10 --connections 300 http://127.0.0.1:8000/ping

Running 30s test @ http://127.0.0.1:8000/ping

10 threads and 300 connections

Thread Stats Avg Stdev Max +/- Stdev

Latency 402.42ms 218.25ms 1.87s 95.23%

Req/Sec 37.59 22.19 130.00 65.35%

10898 requests in 30.07s, 1.83MB read

Socket errors: connect 57, read 133, write 0, timeout 101

Requests/sec: 362.47

Transfer/sec: 62.30KB

The no-GIL runtime did not give a better result than the GIL one. It is puzzling to me.

Performance analysis

I suspect the slowdown comes from

-

using queues / other collections in asynchronous fashion, as queues are implemented with fine-grained locking. It is proved by cryptofeed example using asynio queues underneath.

-

magnified impact from biased and deferred reference counting in production level application

-

Instability in performance due to the stop-the-world GC collector

Conclusion

In running production web applications, the current PoC nogil version does not stand on solid ground yet. I believe this hasn’t come to an end and lots of next stage optimization and improvements can be done. For example, in the current PoC, other mutable collections, e.g. set, are not yet migrated to the optimised thread-safe implementation. Also, many async applications use a lock to ensure the queue is thread safe and it can be removed in PoC nogil. More production level benchmark figures are needed to verify it once a more mutare implementation arrives.

I appreciate Sam Gross’ work and courage to tackle the nogil problem. It is a decade long problem in Python and most believe the endeavour would only be in vain. Part of his work discovered more optimal paths in CPython, has already been merged in main branch and now proves a runtime improvement in Python 3.11. His approach shows his ambition to beat the current CPython performance. Not only does he provide a design to declare the feasibility in nogil approach, but more importantly he is keen to reduce the object readability overhead in thread-safe implementation. No matter his design will be successfully upstreamed into core CPython, his work is a critical milestone in Python.

Finally, I highly recommend walking through his detailed write-up to understand his considerations and rationales in choosing the right bolts and nuts. Also Łukasz Langa posted a great wrap-up in October 2021 in details of conversation between Sam Gross and the core development team. I bet you’d appreciate Sam Gross’ work more after reading them.

Reference

Sam Gross, Python Multithreading without GIL

Backblaze, The Python GIL: Past, Present, and Future, 24th May, 2022