Working in open source projects is fun, but it may also mean to sacrifice one’s personal time to transform amazing ideas into applications. Down the road of development, tedious and routine works are definitely involved. A colossal amount of chores, e.g. documentation, building distributions, and releases, are demanded to keep the project active and also open for contributions.

In the meantime, I have been tired of performing all the routine steps whenever I pronounce “Hey world I have something new for you”. Increasing the granularity in distribution actually penalises my personal time. My question is, “How fast can we generate a new release”?

Distribute Python package

Alike distributing packages in other languages, e.g. Javascript, there are a few steps adapted in the community in package distribution

- Tag releases

- Publish the package to repository

- Maintain changelog

In the open source world, with Github, the above steps is translated as

- Create release tags and push them to Github

- Publish releases to both Github and PyPI

- Maintain the changelog in both documentation and Github release

In the old days, the above steps mean to me

- Use git flow to create release tags

- Use twine to publish packages to PyPI and manually create releases in Github

- Before releasing tags, carefully select the features and fix changes into the changelog

On step 1, I have to wrap up all the important features and hotfixes in the tag commit message and remember to git push --tags always. On step 2, I always grumbled about the duplicated effort to release the same wheels in both Github and PyPI. On step 3, I know most (good) developers keep in mind to update the changelog in each commit, but I can’t keep up the routine in my open source projects.

I am going to walk through my journey of employing poetry, conventional-commit and semantic-release to minimise the package distribution effort, and explain how they can make the distribution procedures lightning fast.

Poetry

Poetry is primarily used for dependency management in development. In development, contributors prefer to maintain a stable working environment (though all the dependent libraries are up-to-dated), and trivially diagnose the glitches and incompatibilities due to dependency version upgrades. The community has evolved from using requirements lock file (produced by pip freeze), then pipenv, to poetry for managing dependency in the environment nowadays. So, with poetry, you can be relieved that, in both the development and release environment, the versions are pinned well.

In the meantime, poetry provides little more assistance in distributing the releases. For example, previously my projects always contain Makefile files, like this,

dist: clean ## builds source and wheel package

python setup.py sdist

python setup.py bdist_wheel

ls -l dist

release: dist ## package and upload a release

twine upload dist/*

and they specify the target like dist and release to build and then distribute the releases. Now these targets are replaced by

poetry build

and then

poetry publish

Most targets in these Makefiles can be migrated to poetry commands. Nailed it.

Conventional commit

The next question is how to maintain the changelog between the release versions. When I was working in a largely scaled vendor providing SaaS to external customers, in each release, both engineers and project managers worked their socks off to ensure correct enhancements or fixes were correctly picked up and then described in the release documentation. I always wondered whether we could optimise those procedures to minimise the chores involved in the release process.

Conventional commit is part of the solution. It can be regarded as a convention, or even a protocol, to standardise the commit message format, so as to allow the devops to automate the release process.

Primarily, the convention requires each commit message is written in below format

<type>[optional scope]: <description>

[optional body]

[optional footer(s)]

Type can be feat (feature), fix, or other descriptive options, e.g. build, chore, ci, docs, style, refactor, perf, test, and others.

Version convention is based on SemVer and releases are based on the commit messages

- Breaking change (either a footer

BREAKING CHANGEor!after type) suggests a major version release. featcommit suggests a minor version releasefixcommit suggests a patch version release

To ensure that every commit message follows the conventional, commitlint can be associated with every CI check.

For example, in Github Action, the commitlint job can be specified like below in yaml configuration

jobs:

# Make sure commit messages follow the conventional commits convention:

# https://www.conventionalcommits.org

commitlint:

name: Lint Commit Messages

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v3

with:

fetch-depth: 0

- uses: wagoid/commitlint-github-action@v4.1.11

Semantic release

Open source tools, e.g. commitizen, are built around the conventional commit ecosystem to automate the changelog update in the past few years. The tool semantic-release not only helps manage the changelog but also automates the full distribution cycle. The idea was first introduced in javascript to publish the packages to the repository platforms. Now it has been extended to Python packages. For example, if your package is hosted in Github, semantic-release will

- update the changelog according to the commit messages

- create tags and distribution packages

- publish the tags, releases and distribution packages to Github, and

- publish the distribution packages to PyPI

By default, you can (and should) always run the command in each push / CI run

semantic-release publish

and it automatically determines whether a new release (and its release version) should be created from the list of commit messages, and performs the full distribution cycle if necessary. The concept is like it automatically creates a new release whenever breaking change, feat or fix type is seen in the git logs, compared to the previous release.

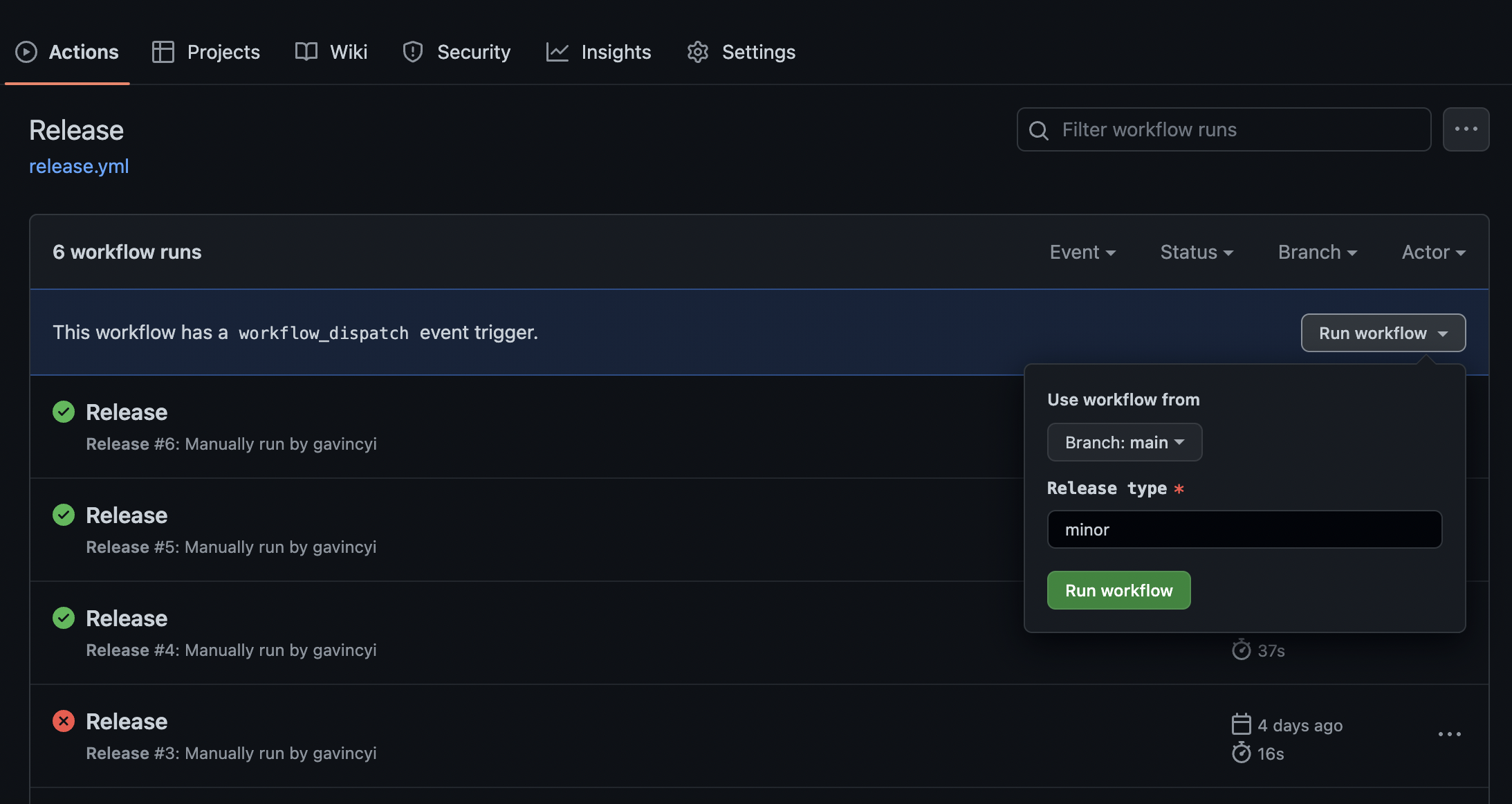

For myself, I am not entirely in faith of automatic release, but happy to use the tool to automate most chores in distribution. So I manually specify the major / minor / patch version upgrade

semantic-release publish --major|minor|patch

whenever I feel necessary. Now it is turned into a GIthub Action in a simple one-click.

For further details, you can refer to a workflow configuration in one of my personal projects.

Conclusion

I recalled when I actively worked on Python open source projects 6 years ago, Makefile and Travis CI were major players in the open source development cycle. It is amazing to see the community evolve from twine, then poetry, and now to semantic-release. All these improvements lead to a more efficient open source development, and also save lots of developers’ (like me) time.

In the meantime, is semantic-release a happy ending of the story? I am afraid not.

I ponder how much these tools are reusable at the enterprise level. For example, poetry can publish the wheels to a private repository, but it seems currently semantic-release assumes to support only the PyPI repository. Also, commit message conventions may be vastly customised at an enterprise level to ensure clarity and compliance requirements during publishing changelog to users / customers. The efforts to create a customer commit parser supported in semantic-release may not be an economic option. Finally, in vendors providing services for multiple customers, the release branches can be greatly diverged. An obvious example is that even after the Python 3.11 version is released, patch versions in Python 3.8 / 3.9 / 3.10 are still actively published. Perhaps the tool caters well for open source development (plainly linear and straight-forward releases) but not entirely in enterprise setup at the moment.

Anyway, I am still happily using the above tools in my open-source development, and it saves my reading time before bed.